Chicago library visit unlocks WWI mystery, shapes Marquardt book

A class trip to Chicago’s flagship library, a non-descript box of old, typewritten letters, and historical intrigue has culminated in a new book compiled and edited by Professor of International Relations James Marquardt with help from student researchers.

The book, Serving the Doughboy, is made up of letters by Mary Frances Willard, a Chicago woman who, at 50, traveled to France during World War I to support American servicemen through an effort organized by the YMCA.

The unmarried, childless public-school principal was among thousands of similar American women who heeded the call. During the war’s final months,  Willard was responsible for setting up and operating a canteen and post exchange, attending to convalescing servicemen, arranging their burials, and writing letters to their families. After the Armistice, she led canteen operations for hundreds of thousands of returning servicemen in embarkation camps. From August 1918 through July 1919, Willard recounted her experiences in weekly letters home that relate stories of her service to the “doughboys”—US infrantrymen—and her interactions with French citizens.

Willard was responsible for setting up and operating a canteen and post exchange, attending to convalescing servicemen, arranging their burials, and writing letters to their families. After the Armistice, she led canteen operations for hundreds of thousands of returning servicemen in embarkation camps. From August 1918 through July 1919, Willard recounted her experiences in weekly letters home that relate stories of her service to the “doughboys”—US infrantrymen—and her interactions with French citizens.

Marquardt discovered Willard’s letters as part of his First-Year Studies course on the causes and consequences of World War I, a class he started in 2014 to mark its centennial outbreak. For the next six years, Marquardt updated the course annually to focus on aspects of the war that occurred roughly 100 years prior.

Discovering the letters

During the traditional Chicago Day visit for all First-Year Studies courses, Marquardt took his students to the Special Collections Archive at the Harold Washington Library Center in downtown Chicago. There an archivist had readied a sampling of the library’s vast collection of war-related artifacts for the students. Among the posters, pamphlets, postcards, and books spread out on long, oak tables sat a cardboard box containing hundreds of typed letters. The pages were copies of Willard’s original letters from France, retyped by her niece and grand-niece decades later.

Leafing through the pages, Marquardt was instantly intrigued and made a mental note to return to the library when he could take a deep dive into their contents. The following summer, he obtained permission to access the box and returned to read through its contents.

“I was motivated, first, because, as a scholar of international relations, I am interested in war and peace studies,” Marquardt said. Once he started reading Willard’s private correspondence to friends and family, Marquardt knew he had stumbled upon something quite special.

“Willard’s letters are a valuable contribution to the literature on women’s work in wartime France. Nearly always written on Sunday evenings, week after week, for 52 weeks, her stories and observations of people, places, and circumstances are vivid,” he said.

With an idea to publish the letters forming, Marquardt consulted with the archivist for information on Willard’s family lineage. Armed with the name of Willard’s niece, Marquardt searched Facebook and quickly made a connection. He found Katherine Burr, who helped her mother retype the fraying original letters that were donated to the Chicago Public Library. When asked about the possibility of publishing the letters, Burr was delighted that her Great-Aunt’s letters, long treasured by the family, might reach a wider audience. “I’ll do whatever you want,” she told Marquardt.

Researching with student help

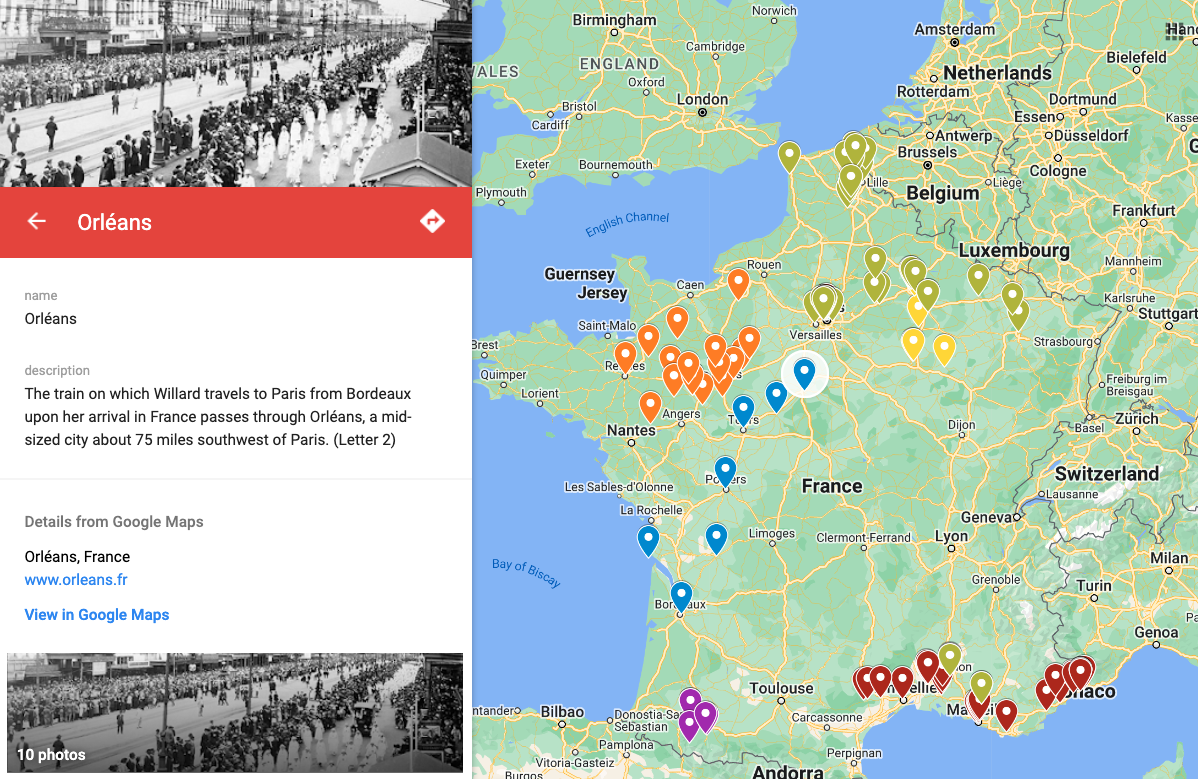

With the family’s permission secured, Marquardt continued to edit the letters, provide important context, and write his introduction all while trying to find a publisher. Once the draft was complete and McFarland & Company of North Carolina agreed to publish, Juan Pérez ’24 spent the summer after his sophomore year working with Marquardt. Pérez selected quotes from Willard’s letters and found photographs of and web links to French cities and landmarks to create “Dear Homefolks,” an interactive digital platform for the public and accompaniment to the book, Serving the Doughboy.

“My primary role was to review each chapter of the book, identifying and cataloging physical places and specific locations mentioned within the text. I mapped additional locations onto an interactive Google Maps template to improve the reader’s experience by providing a dynamic and visual perspective. This enables readers to engage more interactively with the book, as they can navigate through the Google Maps link we incorporated, allowing them to explore the mentioned places in a chronological order as they progress through the narrative,” Pérez said.

Pérez, who is double majoring in international relations and communication and minoring in urban studies, benefited from working as a research assistant on this and other projects during his time at Lake Forest College.

“It helped me understand the ropes of doing research and putting out academic content,” he said. “I also performed other tasks, like collecting data for the international relations department, where I got a good sense of what it could be like to work in academia. I also picked up skills, such as data representation, that I can toss into the mix when applying for future projects.” Peréz intends to work for a year after graduation while he applies to graduate school.

Like many faculty at Lake Forest College, getting students involved in research is key to Marquardt. “It’s an important commitment that we make in the liberal arts,” he said. “It gives students access to what publishing and researching is all about, and it gives them learning opportunities that they typically wouldn’t get otherwise.”